Using Grey & Green Infrastructure for Sustainable & Resilient Design

Originally Published in the BSCES Newsletter.

By Wayne Bates, PhD, PE, Principal Engineer, Tighe & Bond, Inc. and Robert Uhlig, FASLA, LEED AP BD+C, Vice President of Landscape Architecture & Urban Design, Halvorson | Tighe & Bond Studio

For an infrastructure project to be both sustainable and resilient, designers, communities, and stakeholder groups must consider the long-term social, economic, and environmental aspects while at the same time addressing both the expected and the potential risks involved in allowing the asset to remain in continuous service. While the “resiliency” of communities from climate change impacts is receiving much attention, “sustainability” requires that projects are also equitable, inclusive, and adaptive: protecting both our built, and our natural environments.

Historically, engineers have relied on structural solutions, also referred to as “grey infrastructure,” to manage and control storms by preventing them from reaching our built environment. While these systems are critical, they often create a man-made barrier between the natural environment and communities. More recently, engineers and landscape architects have utilized purposefully designed “green infrastructure” elements that use the natural environment to manage storms while providing spaces that benefit nature and society.

As thought leaders in sustainable and resilient design, engineers and landscape architects strive to balance safety, equitable access to the natural environment, and providing a positive experience for the community. The approach and features of several projects worked on by Tighe & Bond and Halvorson | Tighe & Bond Studio are provided below.

Tuscan Village

Tuscan Village is a multi-phased, mixed-use development on the historic Rockingham Park racetrack site in Salem, New Hampshire. The 170-acre site includes both residential and commercial uses, with the South and Central Village portions consisting of approximately 800,000 square feet of retail, office, and residential uses. The vision for this property was to reconnect the development to the natural environment that existed prior to the racetrack, while also providing new features for exercise, exploration, and recreation.

- Figures 1a and 1b- Daylighting of Policy Brook at Tuscan Village

One sustainable feature of this redevelopment is the daylighting of Policy Brook (Figures 1a, 1b, and 1c), which had been culverted to construct the racetrack. The daylighting project created more than 3,000-linear feet of natural stream and adjacent floodplain, which provided opportunities to celebrate and experience the existing brook. Numerous green infrastructure features such as raingardens and a man-made lake resulted in a resilient, sustainable design with direct and indirect benefits. For example, an old irrigation pond that served the former racetrack was restored and redesigned to create the nearly 3-acre Tuscan Lake (Figure 2). The lake helps provide stormwater management for the site and offers outdoor recreational opportunities, including a beach, kayaking, canoeing, and fishing. Adjacent to the lake is Lake Park, which connects the built environment to this man-made natural environment and is a gathering area, with programmable spaces for family activities that overlook the lake.

- Figure 1c- Daylighting of Policy Brook at Tuscan Village

- Figure 2- Tuscan Lake

From a resiliency perspective, replacing the culvert with a natural channel and embankment reduces the impact of storm events both upstream and downstream by reducing peak flows, providing storm surge storage, and incorporating stream calming. The lake and rain gardens also minimize potential storm impacts by reducing peak flows.

Environmentally, daylighting Policy Brook into an open stream with a landscaped embankment improved water quality and created a more robust habitat for aquatic and terrestrial species. The open stream features, combined with other green infrastructure such as the lake and rain gardens (Figure 3), also mitigate the environmental impacts of major storm events.

Figure 3- Green infrastructure rain garden at Tuscan Village

Socially, the daylighted brook, lake, and green infrastructure provide natural resources for Tuscan Village residents and visitors to enjoy year-round. Finally, converting the abandoned racetrack into a sustainable mixed-use development provides an economic benefit to the community, businesses, and residents through increased property values, commercial and rental income, and a re-established tax base.

Senator Joseph Finnegan Park at Port Norfolk

The 14-acre Senator Joseph Finnegan Park at Port Norfolk, located in the Dorchester community of Boston at the mouth of the Neponset River, was transformed from an industrial site—as the former home of the Shaffer Paper Factory—into a neighborhood open space that improves access to the waterfront and restoring a sensitive ecological habitat. This project, on behalf of the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), transformed a previous blemish on the Dorchester neighborhood. Work included cleaning up the site, replacing shoreline flood control features, restoring salt marsh and wetlands, and removing crumbling buildings. Impervious pavement, invasive phragmites, and by-products of industrial activities were replaced with meadow grass, salt marsh, and various tree species which converted the site into a resilient and sustainable natural resource area within an urban environment (Figure 4). With these changes, the natural environment has been reconnected to the built environment with walking trails, resting spots, and landscape architectural features (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 4- Proposed planting schedule for Senator Joseph Finnegan Park

From a resiliency perspective, replacing the grey hardscape with a green softscape creates a natural barrier to reduce the impact of tidal fluctuations and storm events. Environmentally, the remediated site is cleaner, reduces runoff, filters stormwater, increases evapotranspiration, reduces the heat island effect, and provides a wildlife habitat in an urban environment. Socially, the site provides open space to exercise, meditate, meet, and experience nature. In addition, educational signage provides information on the green infrastructure features.

- Figure 5- Conditions of the site before

- Figure 6- Aerial view post-construction

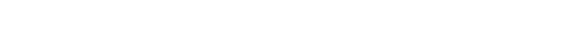

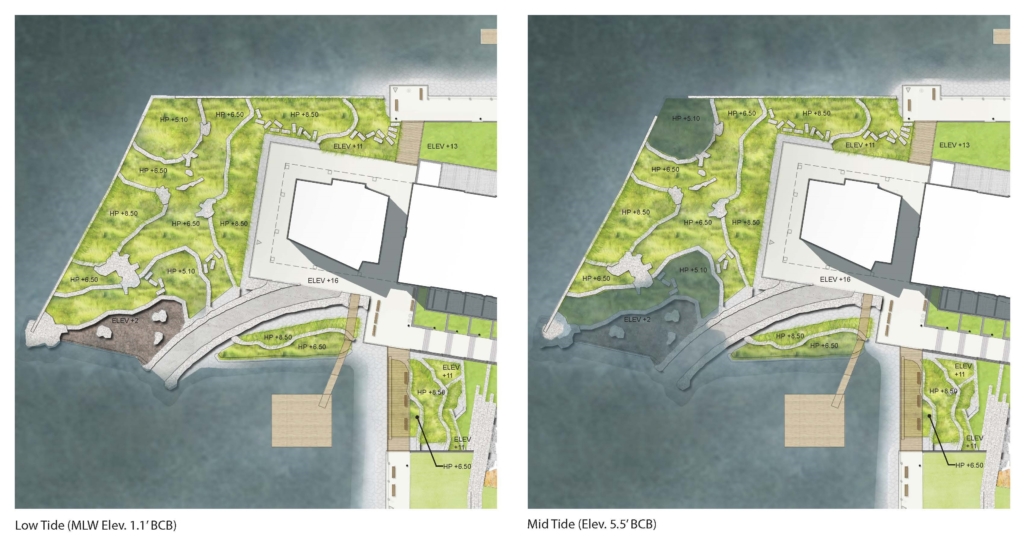

Clippership Wharf and Living Shoreline

Clippership Wharf is a resilient, multi-family residential development and waterfront destination on two abandoned wharves in East Boston. The design protects the site and enhances the waterfront while transforming the open space into passive and active recreation opportunities. With the inclusion of stakeholder engagement, the design considered numerous points of public access to the water and the spectacular views of the Boston skyline, while protecting the built environment. The design includes a tiered site with features that can be submerged during tidal changes (Figure 7) and a harbor walk at the lower level, public access and open spaces at mid-level, and residences and courtyard above. From a resiliency standpoint, the green infrastructure, in the form of open spaces and a living shoreline—featuring saltwater marshes, rocky beaches, and plentiful wildlife habitats—creates a natural flood barrier that protects tenants and other inland properties. Grey infrastructure features, including a stepped seawall and hardened building structures, create a barrier to storm surges and sea-level rise.

Figure 7- Views of Clippership Wharf during low tide (left) and mid tide (right).

Socially, a living shoreline features a connection to the natural environment that people can observe and explore; terraced seawalls provide places for the public to rest and explore; and educational placards and signs demonstrate the function and benefit of the green and grey infrastructure features (Figures 8 and 9). The continuation of the harbor walk across the property provides public access to the water and places for residents and the public to walk, sit, and experience the outdoors. Environmentally, this remediated industrial site reduces the risk of exposure to toxic contaminants and makes the area cleaner and safer. The shoreline and landscape features create a natural environment for people and wildlife, while reducing the impacts of storm events, increasing the pervious area for infiltration, and providing a natural buffer to coastal storm events.

- Figure 8- Clippership Wharf- community access and resource connection

Looking to the Future of Sustainable Design

Resiliency requires that we plan, prepare for, mitigate, and adapt to the changing conditions caused by climate change, and that as a society we must do so to reconnect our built environment to the natural environment. We must continue to take a thoughtful approach to the combination of green and grey infrastructure to achieve sustainable and resilient purpose-built infrastructure that protects the built environment, celebrates the natural environment, and provides both viable and vibrant spaces for people to live, work, and play.